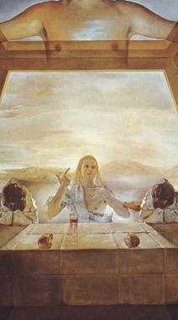

It’s the tradition in our church to observe this solemn occasion – the commemoration of the Last Supper – with communion, followed by a service of tenebrae. Tenebrae is an ancient church tradition in which candles are gradually extinguished as various scripture accounts of Jesus’ passion are read, leaving the sanctuary in total darkness. At the end, the worshipers depart in silence – rather difficult for a group of sociable Presbyterians, but they manage somehow. The service ends on an appropriate tone of solemnity, in preparation for Good Friday.

It’s the tradition in our church to observe this solemn occasion – the commemoration of the Last Supper – with communion, followed by a service of tenebrae. Tenebrae is an ancient church tradition in which candles are gradually extinguished as various scripture accounts of Jesus’ passion are read, leaving the sanctuary in total darkness. At the end, the worshipers depart in silence – rather difficult for a group of sociable Presbyterians, but they manage somehow. The service ends on an appropriate tone of solemnity, in preparation for Good Friday.I’ve known ahead of time that this year’s Holy Week services – including Easter – are not going to be a possibility for me. These worship services all fall during my first week after chemotherapy, which – past experience has taught – is not a time when I have much stamina. Tonight, Claire is preaching in my stead, and helping Robin with the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. I’m sorry to miss it, because it’s one of the outstanding worship services of the year, and our Chancel Choir typically outdoes themselves with the anthems they sing.

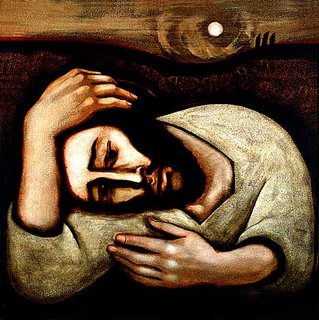

The letter to the Hebrews reflects on Jesus’ agony in the Garden of Gethsemane – when, fearful of the pain of the cross, he prayed to God to “take this cup away from me”:

“In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to the one who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission. Although he was a Son, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and having been made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him, having been designated by God a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek.” (Hebrews 5:7-10)

Jesus’ prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane was not answered. God did not take the cup of suffering away from him. In a similar fashion, my own prayers for good health were not answered. Yet the author of Hebrews assures us that Jesus’ prayer “was heard.” The result was that he was “made perfect” by what he suffered.

“Perfection,” here, probably means more than our ordinary understanding of the word. We generally think of it meaning “without flaw,” but there’s also another meaning to the word. Something that’s “perfect” is complete – as in the perfect tense in English, which describes an action that has been completed. If Jesus’ purpose in coming to earth was to achieve salvation for humanity by dying on the cross, then it’s indeed true that he was “made perfect” by his suffering. As the Easter hymn puts it,

“The strife is o’er, the battle done;

The victory of life is won;

The song of triumph has begun: Alleluia!

The powers of death have done their worst;

But Christ their legions hath dispersed;

Let shouts of holy joy outburst: Alleluia!”

I’ve got to trust that this ordeal I’m going through – not worth comparing to crucifixion, certainly, but it’s suffering all the same – is preparing me for something, somehow. The outcome of Jesus’ suffering, according to Hebrews, is that he was able to serve as “a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek.” I have no interest in the high-priest business, but I’d settle for the capacity to fulfill my priestly role as a minister a little better. The classic role of a priest is to stand between God and the people, serving as a mediator. We Protestants long ago rejected the idea that the celebration of the Lord’s Supper is a priestly role – that’s why we have a communion table instead of an altar. We also no longer believe that one must be ordained in order to hear another’s confession and pronounce absolution. Yet we ministers have hung on to the idea that we echo Christ’s priestly role, as we preach and visit and listen and serve. Maybe, as a cancer survivor, I’ll be better equipped for the priestly ministry of compassion.