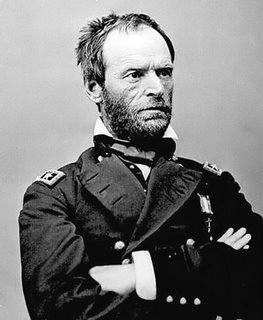

One of the most frustrating aspects of civilization's war against terrorism is that the adversaries are so hard to find. Something similar is true of cancer: it's only in certain circumstances that the enemy is clearly defined, and can be efficiently removed with a "surgical strike." More often than not, malignant cells linger, even after the scalpel's intervention. Grueling "therapies" – chemical, radiological – put the patient through hell, for a still-inconclusive outcome. But that should come as no surprise. "War is hell," said the infamous General Sherman, recalling the plumes of black smoke rising over the rooftops of Atlanta.

One of the most frustrating aspects of civilization's war against terrorism is that the adversaries are so hard to find. Something similar is true of cancer: it's only in certain circumstances that the enemy is clearly defined, and can be efficiently removed with a "surgical strike." More often than not, malignant cells linger, even after the scalpel's intervention. Grueling "therapies" – chemical, radiological – put the patient through hell, for a still-inconclusive outcome. But that should come as no surprise. "War is hell," said the infamous General Sherman, recalling the plumes of black smoke rising over the rooftops of Atlanta. Yet, there's something about the military metaphor, applied to cancer, that doesn't quite fit. Cancerous cells are not some foreign invader: a band of terrorist commandos who slip across the border on forged passports, to blow themselves up, and us along with them. Cancer cells spring from our own loins. They arise from out of our own bodies, the result of genetic mutations that, despite science's best efforts, are still only dimly understood. If the terrorist metaphor applies at all, it's Timothy McVeigh and the Federal Building in Oklahoma City, not al-Qaeda and 9/11. We cancer survivors have met the enemy, and he is us.

Yet, there's something about the military metaphor, applied to cancer, that doesn't quite fit. Cancerous cells are not some foreign invader: a band of terrorist commandos who slip across the border on forged passports, to blow themselves up, and us along with them. Cancer cells spring from our own loins. They arise from out of our own bodies, the result of genetic mutations that, despite science's best efforts, are still only dimly understood. If the terrorist metaphor applies at all, it's Timothy McVeigh and the Federal Building in Oklahoma City, not al-Qaeda and 9/11. We cancer survivors have met the enemy, and he is us.I've quoted before from a little book of devotions called Now That I Have Cancer, I Am Whole, by John Robert McFarland (Andrews and McMeel, 1993). McFarland is a Methodist minister and colon-cancer survivor. Suzanne, a minister-colleague of mine and a friend of McFarland's, gave the book to me not long after I was diagnosed. Here's what he has to say about cancer and wholeness:

"In trying to beat cancer... I am competing against myself. Cancer is a part of me, so if I win, I also lose. Getting whole, getting well, has to do with oneness. It's not a matter of right or wrong, victory or defeat, not even life or death. It is life vs. nonlife. If I experience wholeness in life, death is not a defeat. If I experience fragmentation in life, then life is not a victory.

The goal, the sense of purpose, is not so much getting cured, beating the cancer, continuing to live. The goal is wholeness itself, being a full and complete person. That is adequate purpose. In fact, it is the only worthy purpose of life. I don't have to make some great achievement, do some mighty work, to justify my existence. Being a whole person is the purpose for our being.

There is no single road to wellness. Getting well and being well is taking an interlocking network of highways that lead to the one, central junction of wholeness" (p. 48).

I’ve been thinking about my PET Scan report, that – as I read the medical jargon, anyway – indicates no sign of malignancy. That’s good news, something to celebrate. Yet, I also know, from my reading about Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, that oncologists generally prefer to use the word “remission,” rather than “cure,” when talking about this kind of cancer.

It takes millions of malignant cells to create even the tiniest “hot spot” on the PET Scan film. That means hundreds of thousands of those cells could still be holed up in some dark, Tora-Bora cave within my body, subsisting below the radar of even the most sophisticated medical test – and the doctors know it. Even if the chemotherapy drugs and the Rituxan have wiped out every last malignant cell in my body, there’s nothing to stop some normal cell from going through the same mutation, starting the process all over again. If lymphoma’s plan of attack is coded into my DNA – as is entirely possible, and even likely – then who can prevent its return? There’s not a lot of closure, in treating NHL.

It takes millions of malignant cells to create even the tiniest “hot spot” on the PET Scan film. That means hundreds of thousands of those cells could still be holed up in some dark, Tora-Bora cave within my body, subsisting below the radar of even the most sophisticated medical test – and the doctors know it. Even if the chemotherapy drugs and the Rituxan have wiped out every last malignant cell in my body, there’s nothing to stop some normal cell from going through the same mutation, starting the process all over again. If lymphoma’s plan of attack is coded into my DNA – as is entirely possible, and even likely – then who can prevent its return? There’s not a lot of closure, in treating NHL.Evidently, that's true of some other forms of cancer, as well, as McFarland observes:

"Cure is an end-result concept. Wellness, health, healing, wholeness – these are process, each-moment-at-a-time concepts. I don't just want to be cured, to reach the end of one road. I want to be whole for each moment of all my life, whether my days are few or many" (p. 49).

I’m beginning to realize that this is the road map for my future. It’s always been the road map – indeed, it is for all of us – but the cancer experience reveals it with particular clarity.

You can’t wage war against cancer, any more than you can wage war against terrorism (as our nation is slowly learning). There are certain battles you can fight, but there’s no final resolution. The solution lies somewhere else. It lies within ourselves – where, by the grace of God, we may one day receive the wisdom to find it.