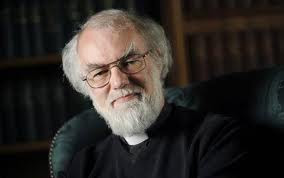

He gets an awful lot of stick, mainly from the BBC and The Daily Telegraph, and very occasionally from His Grace, but only when it is deserved. The media decided long ago to be unanimously unkind to him, principally because he thinks in paragraphs, talks in complex polysyllables and has distracting eyebrows. His Grace has met his successor on a number of occasions, and he is far more congenial, respectful and listening than any politician he has ever met (and that numbers hundreds, of all parties). Archbishop Rowan is a gifted pastor and an intelligent theologian: he is a man of great humility and considerable spirituality.

He just isn’t much of a leader.

He just isn’t much of a leader.But neither was Iain Duncan Smith.

And while Mr Duncan Smith has discovered his undoubted metier – that of Beveridge the Sequel, crusading against ‘want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness’ – there is a sense in which you feel that Rowan Williams is still in search of his.

He had a bit of a bad hair day yesterday: five bishops defected to the Bishop of Rome, and he ventured an opinion on IDS’s welfare reforms.

As a result, he was mocked, insulted, scorned and lambasted. One blogger, Mark Wallace, who describes himself as a ‘political campaigner, writer and angry young man’, alerted His Grace via tweet message to his post on the matter, remarking that he 'doesn’t normally foray into religion’.

As a result, he was mocked, insulted, scorned and lambasted. One blogger, Mark Wallace, who describes himself as a ‘political campaigner, writer and angry young man’, alerted His Grace via tweet message to his post on the matter, remarking that he 'doesn’t normally foray into religion’.And so he asks in his opening line: ‘What exactly is the point of Rowan Williams?’

His Grace has never met Mr Wallace, who seems to be a perfectly splendid and decent sort of chap.

But he really shouldn’t have forayed into religion without doing a bit of homework.

As one of his commentators observed: “…one or two absurd remarks doth not a pointless person make.”

Indeed it does not.

Otherwise David Cameron would be pointless.

But he is needed to lead the Executive.

And Ed Miliband would be pointless.

But Parliamentary democracy needs a loyal Opposition.

And then there's Nick Clegg.

O, hang on.

There might be one or two exceptions.

But Mr Wallace asked His Grace to respond to his post about ‘meddlesome’ and ‘misguided’ priests, and so he will.

The ‘point’ of Rowan Williams is evident to all who have ears; to all who understand history, the religio-political function and purpose of the Monarchy, the development of our system of government and the checks and balances which have evolved over the centuries to limit the exercise of absolute and arbitrary power.

The ‘point’ of Rowan Williams is evident to all who have ears; to all who understand history, the religio-political function and purpose of the Monarchy, the development of our system of government and the checks and balances which have evolved over the centuries to limit the exercise of absolute and arbitrary power.The Church of England was once referred to as being ‘crucified between two thieves’. While this reference was to the respective fanaticism and superstition of ‘the Puritans and the Papists’, there is a modern parallel with a church now suspended between the decline in institutional religion and the burgeoning of generalised ‘spirituality’; between the secularisation of society and the plurality of faith communities. The postmodern context is marked by diversity, fragmentation and all that is transitory; beliefs and practices are culturally relative, and Anglicanism has ceased to be supra-cultural or catholic.

The Church has always struggled with the tension between the affirmation and assimilation of culture, and the call of the gospel to confront and transform it, which remains the Queen’s ultimate raison d’être. Niebuhr outlined five possible relationships between the gospel and culture, which are the typical answers given in Christian history. His Christ against culture; of culture; above culture; with culture in paradox; and Christ the transformer of culture, each generate different understandings of the mission of the Church. And each finds its expression in the ‘broad church’ that is the Church of England – which incorporates Protestants, Evangelicals, conservatives, liberals, Anglo-Catholics (minus five) and permutations of various fusions of these held ‘in tension’.

The Church has always struggled with the tension between the affirmation and assimilation of culture, and the call of the gospel to confront and transform it, which remains the Queen’s ultimate raison d’être. Niebuhr outlined five possible relationships between the gospel and culture, which are the typical answers given in Christian history. His Christ against culture; of culture; above culture; with culture in paradox; and Christ the transformer of culture, each generate different understandings of the mission of the Church. And each finds its expression in the ‘broad church’ that is the Church of England – which incorporates Protestants, Evangelicals, conservatives, liberals, Anglo-Catholics (minus five) and permutations of various fusions of these held ‘in tension’. Historically, some archbishops have viewed culture as antagonistic to the gospel, and adopted a confrontational approach. Others have seen culture as being essentially ‘on our side’, adopting the anthropological model of contextualisation, looking for ways in which God has revealed himself in culture and building on those.

Those who adopt the ‘Christ above culture’ model have a synthetic approach and adopt a mediating third way, keeping culture and faith in creative tension. And those who see Christ as the transformer of culture adopt a critical contextualisation which by no means rejects culture, but is prepared to be critical both of the context and of the way we ourselves perceive the gospel and its meaning. Thus culture itself needs to be addressed by the gospel, not simply the individuals within it, and truth is mediated through cultural spectacles, including those performed at great state events by the Church of England, which are inimitable.

Those who adopt the ‘Christ above culture’ model have a synthetic approach and adopt a mediating third way, keeping culture and faith in creative tension. And those who see Christ as the transformer of culture adopt a critical contextualisation which by no means rejects culture, but is prepared to be critical both of the context and of the way we ourselves perceive the gospel and its meaning. Thus culture itself needs to be addressed by the gospel, not simply the individuals within it, and truth is mediated through cultural spectacles, including those performed at great state events by the Church of England, which are inimitable. This latter model mitigates cultural arrogance or easy identification of the gospel with English culture. It also permits one to see how mission relates to every aspect of a culture in its political, economic and social dimensions, which is what has brought the Archbishop of Canterbury into conflict with Iain Duncan Smith.

The task of the Church (and so the Archbishop of Canterbury) is to challenge the reigning plausibility structure by examining it in light of the revealed purposes of God contained in the biblical narrative. Archbishop Rowan essentially advocates a scepticism which enables one to take part in the political life of society without being deluded by its own beliefs about itself: Establishment commits the Church to full involvement in civil society and to making a contribution to the public discussion of issues that have moral or spiritual implications.

No-one can easily deny that the ministry of Iain Duncan Smith is not contiguous with the ministry of the Church of England: Jesus cared for the poor; indeed, Luke’s Gospel is a message of undoubted privilege for them. IDS is driven with Christian missionary zeal to minister to the most vulnerable of society. For what it’s worth, His Grace agrees wholly with IDS on this matter.

But he also wishes to point out, yet again, that the Archbishop of Canterbury has been woefully misunderstood and misreported by a ferociously judgmental hostile press.

But he also wishes to point out, yet again, that the Archbishop of Canterbury has been woefully misunderstood and misreported by a ferociously judgmental hostile press. By talking of ‘spirals of despair’ in which the unemployed might find themselves, he concerns himself with the pastoral dimensions of wholeness and healing. Archbishop Rowan is persuaded that the mission of the Church accords with people’s quest for meaning and an assurance of identity which cannot be found without community, without fellowship. It is this which the Archbishop was addressing: he was not advocating unlimited benefits for the indolent and workshy.

Notwithstanding some of the excellent work going on in some of the most impoverished parishes in the country, the public perception of the Church of England remains one of middle-class privilege and an élitism which has little relevance to a modern, pluralist, multi-ethnic society. While this is an undoubted misconception, it is exacerbated by the nature of establishment and the fusion of the Church with an increasingly secular government.

And yet it is within this relationship that there remains one of the Church’s primary functions in holding government and political parties to account. The document ‘Moral but no Compass’, although unofficial, illustrated the powerful role the Church of England may still exercise in highlighting the inadequacies - spiritual and political - of the governmental system, in order that people’s welfare may be improved. Whatever the outcome of the Archbishop’s words, the intervention suggests that the public realm remains an arena in which the Church’s moral and ethical mission continues to be exercised. Perhaps it is only the Establishment Church that, in contemporary society, possesses the status to permit it to fight for representation of a slighted electorate in the face of an increasingly abstract political élite.

And yet it is within this relationship that there remains one of the Church’s primary functions in holding government and political parties to account. The document ‘Moral but no Compass’, although unofficial, illustrated the powerful role the Church of England may still exercise in highlighting the inadequacies - spiritual and political - of the governmental system, in order that people’s welfare may be improved. Whatever the outcome of the Archbishop’s words, the intervention suggests that the public realm remains an arena in which the Church’s moral and ethical mission continues to be exercised. Perhaps it is only the Establishment Church that, in contemporary society, possesses the status to permit it to fight for representation of a slighted electorate in the face of an increasingly abstract political élite. While the Archbishop’s observations may or may not be valid or politically astute, they add to the perception that the Church of England seeks to exclude or is out of sympathy with some distinct groups of people, in this case the Government or fans of IDS.

Hence the vitriol from Conservative-supporting blogs.

But it must be remembered that the Church’s Supreme Governor is also the Head of State, and by virtue of being so she is obliged to exercise her public ‘outward government’ in a manner which accords with the private welfare of her subjects – of whatever social status, creed, ethnicity, sexuality or political philosophy. The Royal Supremacy in regard to the Church is in its essence the right of supervision over the administration of the Church, vested in the Crown as the champion of the Church, in order that the religious welfare of its subjects may be provided for.

While theologians and politicians may argue over the manner of this ‘religious welfare’, especially, it seems, in the provision of benefits, the Archbishop speaks because the Head of State cares and cannot speak. He may not always speak as she would wish to, but by speaking at all he reminds us that there is something which transcends the scurvy politicians, who, as the Bard observed, have an annoying habit of seeming to see the things they do not.

We are no longer in an age, if ever we were, where the Archbishop of Canterbury can impose a morality or a doctrine of God, and Archbishop Rowan sees his primary function as being the acutely political one of calling the state to account by obstinately asking the state about its accountability and the justification of its priorities.

We are no longer in an age, if ever we were, where the Archbishop of Canterbury can impose a morality or a doctrine of God, and Archbishop Rowan sees his primary function as being the acutely political one of calling the state to account by obstinately asking the state about its accountability and the justification of its priorities.He may occasionally be a thorn in the side of government.

But it is better to have a benign and occasionally misguided Anglican one than a monolithic, absolute and malignant one…

…if you have ears to hear.